Where to publish a story in 2024

The new publishing landscape

Welcome back to your weekly ARC Worlds missive!

Last week’s reader poll still has a few minutes left of life. Based on the votes in last week’s reader poll, it seems like I am the most popular writer on the Internet, right after .

Don’t believe me? Check out the poll here.

OK, you’re back.

If you looked at the poll relating to what topics interest ARC Worlds readers the most, you would have seen that “behind-the-scenes author life” was far and away the top choice.

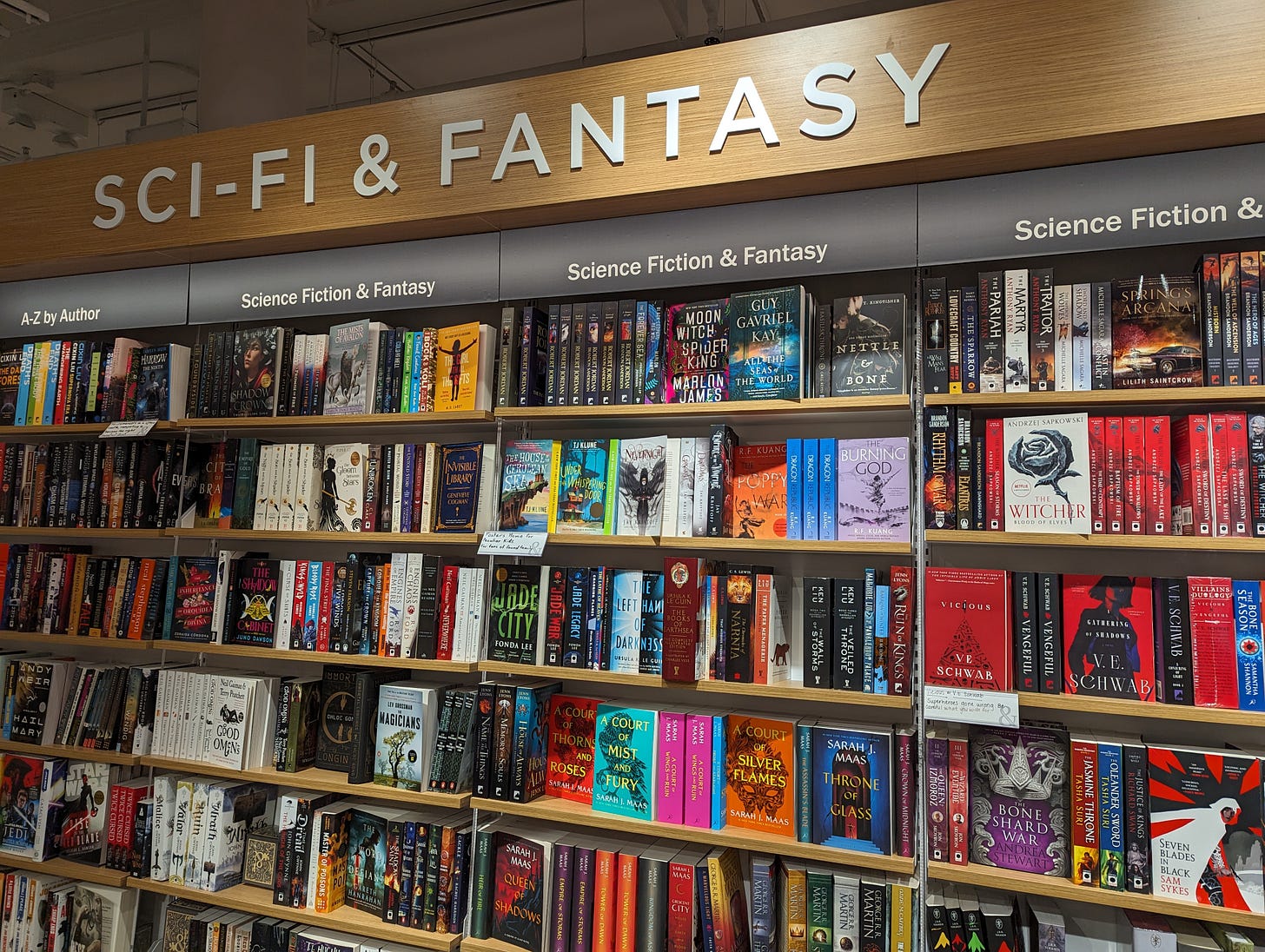

With that in mind, today’s post is going to be a brief overview of the fantasy publishing landscape in 2024.

Let’s say I had just finished writing a new fantasy book series or a short story.

What are my options to getting this story to readers?

Traditional publishing

After decades of consolidation, there are only five large publishing houses left (with Penguin Random House trying but failing to buy Simon & Schuster a few years ago). These houses over time bought up the vast majority of science fiction and fantasy imprints, which are brands/labels within the houses that publish genre-specific books.

To get my book published by a traditional publisher, I would need to be represented by a literary agent, as they do not take unsolicited submissions. To acquire a literary agent, I would need to send a query letter to my agents of choice, who ideally have experience selling science fiction and fantasy books to the publishing houses, and hope that they agree to take me as a client.

If they do, they will likely require more edits to the manuscript, before it is submitted to publishers. Should a publisher end up buying my manuscript (or perhaps a three-book deal for a series), the publisher will edit the book further and then place my book in a slot on their release calendar perhaps a year or more away. They will work with book distributors/wholesalers to get my book into bookstores around the country and via e-commerce sites on release day, gauging the size of the initial print run by the number of pre-orders. Absent my book being the subject of a seven-figure bidding war, there will be perhaps 2-3 copies of my book available in my local bookstore (if any) on release day.

Traditionally, publishers concentrated their marketing efforts on selling their books to their customers, which were the bookstores, wholesalers, and distributors. With the number of retail locations to buy books rapidly shrinking (you used to be able to buy books regularly in the grocery store) and with the Internet allowing readers to buy any book from anywhere in the country (and the world), publishers belatedly realized that they needed to market their books (and their brands) more to the actual end-user, the reader. So they have invested more time and money in building the consumer-facing side of their brands, with newsletters, social media accounts, and giveaways. However, most traditionally published fantasy authors still find themselves responsible for the majority of the marketing efforts behind their book.

One final thing to remember about traditional publishing: you cannot choose to be traditionally published. It is something that external parties will determine for you.

Genre magazines

In the hey-day of publishing, in addition to the numerous publishers, there were also monthly science fiction and fantasy magazines, where writers could submit short stories or serialize their novels (the first three entries in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series were in fact first published as novellas in Astounding Science Fiction before being collected into novels). Although some of these magazines are still around today, like the rest of the magazine industry, their financial viability has unfortunately declined.

That being said, genre magazines remain an important part of the science fiction and fantasy ecosystem. And unlike traditional publishers, who take your stories for the rest of your life, magazines merely license first-publication rights and some reprint rights. Meaning I can sell a short story to a magazine, get paid for it, and then release that same story in my own collection later on.

Indie publishing via Amazon

For all its faults, Amazon was one of the first booksellers to allow indie authors to publish directly on its store. That, coupled with the ubiquity of the Kindle e-reader, meant that indie authors in the early 2010s were suddenly able to reach readers easily and (somewhat) directly. All that was required was a formatted ebook file, a cover, and some metadata. Although there were a lot of books published that should not have seen the light of day, many authors, who would not have made it down the traditional publishing pipeline described above, were having great success.

As the number of authors publishing on Amazon grew, so did the launch of new revenue models (Kindle Unlimited), new tools for those authors, and new ways to publicize books (Facebook & Amazon Ads). Gone were the days when you had to code your book into an HTML file, to then have it converted into the e-book format. (Yes, I actually did this for my first novelette, but thankfully only that one time). There were programs that did one-click formatting, pre-made covers, newsletter providers, and more. It was a lot to learn and digest, but thankfully, with the burgeoning number of indie authors soon came others who distilled what they had learned into how-to books and Facebook groups where like-minded authors could congregate.

However, there eventually reached a saturation point, where the amount of organic visibility started decreasing, such that authors who relied on Amazon to recommend their books to readers for them (without paying for ads) were finding it harder and harder to get noticed within the sea of new releases.

Serial fiction sites

At the same time authors were flocking to Amazon, others headed to serial fiction websites, like Wattpad and Royal Road. These sites completely cut out the middleman; it was just the writer posting individual chapters to voracious readers, oftentimes multiple times a week. Stories stretch on for months and years, and readers reward consistent posting. Each site’s readers have their own proclivities, with Royal Road favoring isekai and LitRPG, and Wattpad skewing more young adult.

I started posting Guild of Tokens chapters to Royal Road when I started this Substack (although at a slower pace) as a way to reach readers there, hoping that some would subscribe to my Substack to read ahead. While that hasn’t really happened for the NYC Questing Guild series, I’m hopeful that some of my other projects will be more successful there.

Direct first, sell everywhere

With decreasing visibility on e-commerce platforms, lower payouts in Kindle Unlimited, and higher advertising costs, more and more authors over the past two years have been transitioning to a direct selling approach.

What does that mean?

A lot of things.

It means maintaining their own online storefronts, where they can sell ebooks and physical books for the same price (or less) and keep more of the money.

It means launching books first on Kickstarter, pre-selling hundreds of copies, and then directly mailing books to eager readers.

It means being retailer agnostic, abandoning the forced exclusivity of Kindle Unlimited to instead sell on every possible retail platform.

It means subscription websites like Substack and Patreon.

New avenues and channels are popping up seemingly every month, but astute authors will find what works for them and start building deeper relationships with their readers.

I hope this was a good overview from the top-down on how stories can make their way to readers.

Thank you and keep writing.

Thanks for this post. I find myself in the crossroads and sometimes I still want the trad and other times I just want to self-pub and go wide. Right now, just focusing on increasing my substack and gaining a following for my stories.